Maya News Updates 2008, No. 20: Copan, Honduras - Research on 5th Century AD Textiles found in 2004

On Wednesday April 16, 2008, the online science monitor NewsWise.com posted a short report on the research of Maya textiles as found in a 5th century AD tomb in 2004 in Copan, Honduras. The report, which details research by textile specialist Margaret Ordoñez, professor at the University of Rhode Island and director of the Historic Textile and Costume Collection, discusses for instance the techniques used by the ancient weavers and how close these are to modern day techniques (edited by MNU):

Analysis of Rare Textiles from Honduras Ruins Suggests Mayans Produced Fine Fabrics - Very few textiles from the Mayan culture have survived, so the treasure trove of fabrics excavated from a tomb at the Copán ruins in Honduras since the 1990s has generated considerable excitement.

Textiles conservator Margaret Ordoñez, a professor at the University of Rhode Island, spent a month at the site in 2004 examining 100 textile samples found in a tomb, and since then she has been analyzing tiny fragments of 49 samples she brought back to her lab to see what she could learn from them.

The tomb, one of three excavated by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania, was of a woman of high status who was buried during the 5th century. “What was most amazing was that there were as many as 25 layers of fabrics on an offertory platform and covering pottery in the tomb, and they all had a different fabric structure, color, and yarn size, so it’s likely that the tomb was reopened – perhaps several times -- and additional layers of textiles were laid there years after her death,” said Ordoñez.

One fabric in particular had an especially high thread count – 100 yarns per inch – which Ordoñez said is even considered high for modern textiles. “It speaks to the technology they had at the time for making very fine fabrics. It’s gratifying that we’ve been able to document that the Mayans were quite skillful at spinning and weaving.”

Analyzing these ancient textile samples is a complex and laborious process, particularly because the remnant samples are so small. Ordoñez pulled out about 30 plastic containers the size of a film canister, and inside each was what looked like a rock or bit of compressed mud about an inch in diameter. Within each piece were flecks of what only an expert could tell are tiny fragments of fabric.

“Sometimes you really have to use your imagination to tell that there’s a textile in there,” she said. Handling each piece very carefully so it doesn’t crumble, Ordoñez uses a stereomicroscope to examine the yarn structure, the fabric structure, and the finish on each sample. She then brings the sample to the URI Sensors and Surface Technology Laboratory to use a scanning electron microscope to look in more fine detail at the plant material from which each piece of yarn was made.

“I can look at the cell structure of the yarn and compare it to reference materials to identify the kind of plant each thread is made from,” explained Ordoñez, who may spend as many as three days examining each fragment. “We’ve found threads made from cotton, sedge grasses, and all kinds of other plant fibers.”

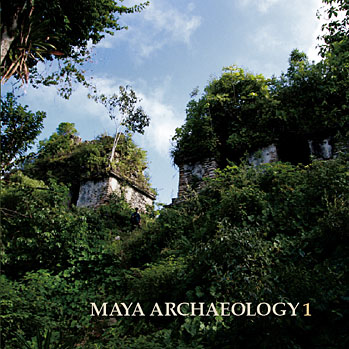

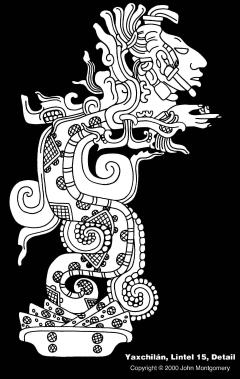

After completing the analysis of the textile samples in her lab this summer, the URI professor plans to return to the Copán ruins in 2009 to examine more fragments from the woman’s tomb and other sites. She said the working conditions at the site are challenging and the research facilities are primitive, but the site provides the best opportunity to learn more about the Mayan culture. She may even do a study of Mayan statuary at the site to see what she can learn from the way that sculptors represented textiles from the period (source Newswise).

Textiles conservator Margaret Ordoñez, a professor at the University of Rhode Island, spent a month at the site in 2004 examining 100 textile samples found in a tomb, and since then she has been analyzing tiny fragments of 49 samples she brought back to her lab to see what she could learn from them.

The tomb, one of three excavated by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania, was of a woman of high status who was buried during the 5th century. “What was most amazing was that there were as many as 25 layers of fabrics on an offertory platform and covering pottery in the tomb, and they all had a different fabric structure, color, and yarn size, so it’s likely that the tomb was reopened – perhaps several times -- and additional layers of textiles were laid there years after her death,” said Ordoñez.

One fabric in particular had an especially high thread count – 100 yarns per inch – which Ordoñez said is even considered high for modern textiles. “It speaks to the technology they had at the time for making very fine fabrics. It’s gratifying that we’ve been able to document that the Mayans were quite skillful at spinning and weaving.”

Analyzing these ancient textile samples is a complex and laborious process, particularly because the remnant samples are so small. Ordoñez pulled out about 30 plastic containers the size of a film canister, and inside each was what looked like a rock or bit of compressed mud about an inch in diameter. Within each piece were flecks of what only an expert could tell are tiny fragments of fabric.

“Sometimes you really have to use your imagination to tell that there’s a textile in there,” she said. Handling each piece very carefully so it doesn’t crumble, Ordoñez uses a stereomicroscope to examine the yarn structure, the fabric structure, and the finish on each sample. She then brings the sample to the URI Sensors and Surface Technology Laboratory to use a scanning electron microscope to look in more fine detail at the plant material from which each piece of yarn was made.

“I can look at the cell structure of the yarn and compare it to reference materials to identify the kind of plant each thread is made from,” explained Ordoñez, who may spend as many as three days examining each fragment. “We’ve found threads made from cotton, sedge grasses, and all kinds of other plant fibers.”

After completing the analysis of the textile samples in her lab this summer, the URI professor plans to return to the Copán ruins in 2009 to examine more fragments from the woman’s tomb and other sites. She said the working conditions at the site are challenging and the research facilities are primitive, but the site provides the best opportunity to learn more about the Mayan culture. She may even do a study of Mayan statuary at the site to see what she can learn from the way that sculptors represented textiles from the period (source Newswise).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home