Maya News Updates 2008, No. 17: A Column by Walter Witschey

Not a real news item, but the column by Walter Witschey, posted on Thursday March 27, 2008, at InRich.com, touches upon two epiphanies through which many a Maya researcher may have been (edited by MNU):

Opportunity, frustration at a Maya temple site - The opportunities and the limitations of science catch us by surprise. I had such an epiphany 10 days ago in Balamku, an unlikely out-of-the way place on the truckers' highway from Escarcega to Chetumal, Mexico.

The paved two-lane road crosses the base of the Yucatan Peninsula about 50 miles north of the northern border of Guatemala. It is a major connector between eastern Mexico and Mexico City. I've traveled the road quite a few times, the last time in 1990. The road has a number of ancient Maya ruins along it. Becan, an unusual site fortified with a moat, is there. It was a defensive posture taken out of concern for its powerful and aggressive rival to the south in the Late Classic (600-800 AD). Chicanna is there, named for its striking structure with a monster-mouth doorway (in Maya, chi is mouth, can is serpent, and na is house -- together serpent-mouth-house.)

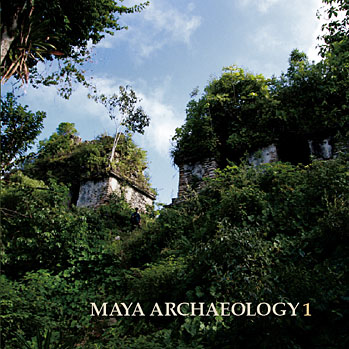

I had not visited Balamku (in English, Jaguar-temple). It was after my last trip across the peninsula, in 1990, that archaeologist Florentino Garcia Cruz, of the state archaeology office of Campeche, Mexico, and the National Institute of Anthropology and History, discovered the site by accident. The first part of the epiphany is that of discovery and opportunity. I had passed within 2 miles of this place numerous times without ever having a clue that an astonishing Maya site, with well-preserved bas-relief stucco, lay so close. It dates to about AD 600.

The same could be said of the thousands of other people who have traveled the highway in past years. For all our research and investigation, whether in archaeology, cell biology, chemistry or genetics, new discoveries wait for us just a few yards off the well-traveled highway. With insight and good fortune, they become our discoveries.

The paved two-lane road crosses the base of the Yucatan Peninsula about 50 miles north of the northern border of Guatemala. It is a major connector between eastern Mexico and Mexico City. I've traveled the road quite a few times, the last time in 1990. The road has a number of ancient Maya ruins along it. Becan, an unusual site fortified with a moat, is there. It was a defensive posture taken out of concern for its powerful and aggressive rival to the south in the Late Classic (600-800 AD). Chicanna is there, named for its striking structure with a monster-mouth doorway (in Maya, chi is mouth, can is serpent, and na is house -- together serpent-mouth-house.)

I had not visited Balamku (in English, Jaguar-temple). It was after my last trip across the peninsula, in 1990, that archaeologist Florentino Garcia Cruz, of the state archaeology office of Campeche, Mexico, and the National Institute of Anthropology and History, discovered the site by accident. The first part of the epiphany is that of discovery and opportunity. I had passed within 2 miles of this place numerous times without ever having a clue that an astonishing Maya site, with well-preserved bas-relief stucco, lay so close. It dates to about AD 600.

The same could be said of the thousands of other people who have traveled the highway in past years. For all our research and investigation, whether in archaeology, cell biology, chemistry or genetics, new discoveries wait for us just a few yards off the well-traveled highway. With insight and good fortune, they become our discoveries.

The same Jaguar-temple place provided the other epiphany as well -- science is limited in what it can tell us. One of the sharpest limitations we have is our ability to see into the minds of those long dead.

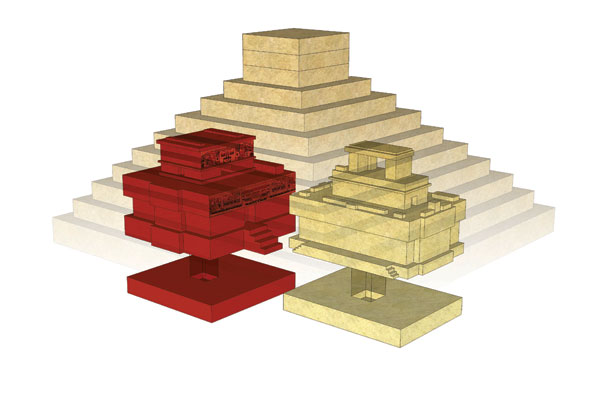

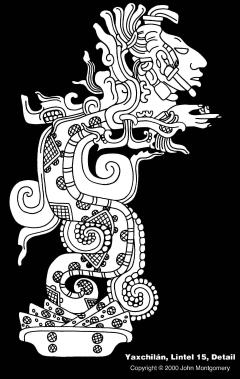

At Balamku, the stucco mural frieze stretches more than 60 feet across a building facade. In typical Maya fashion, the building was enclosed within a later structure, which served to protect it. Today, the frieze is protected by a modern enclosure (which on the outside reproduces the look of the original outside temple). The cosmological picture portrayed by the Maya rulers is well beyond our modern science to unravel. We can guess, but we cannot know.

While we do know much about the ancient Maya, we are still face-to-face with one of the great shortcomings of science. We cannot know the minds of those who went before us. We think we understand their symbols, their analogies, and their belief system, but do we really? We cannot. Their art, artistry and cosmology attest to a complex worldview and a hungry human spirit. Our science can save the stucco, but not the powerful ideas in the minds of its creators (written by Walter Witschey; source InRich.com) (photograph of part of the Balamku frieze by Sven Gronemeyer).

At Balamku, the stucco mural frieze stretches more than 60 feet across a building facade. In typical Maya fashion, the building was enclosed within a later structure, which served to protect it. Today, the frieze is protected by a modern enclosure (which on the outside reproduces the look of the original outside temple). The cosmological picture portrayed by the Maya rulers is well beyond our modern science to unravel. We can guess, but we cannot know.

While we do know much about the ancient Maya, we are still face-to-face with one of the great shortcomings of science. We cannot know the minds of those who went before us. We think we understand their symbols, their analogies, and their belief system, but do we really? We cannot. Their art, artistry and cosmology attest to a complex worldview and a hungry human spirit. Our science can save the stucco, but not the powerful ideas in the minds of its creators (written by Walter Witschey; source InRich.com) (photograph of part of the Balamku frieze by Sven Gronemeyer).