Maya News Updates 2008, No. 52: Recently Published Research - A Zooarchaeological Test for Dietary Resource Depression at the End of the Classic Period in the Petexbatun, Guatemala

In the recent issue of Human Ecology (Vol. 36, No. 5: 617-634, published by Springer) an article can be found written by Dr. Kitty Emery. Her research on ancient Maya animal use has been the subject of a previous Maya News Update (2007, No. 75). The article in Human Ecology is entitled "A Zooarchaeological Test for Dietary Resource Depression at the End of the Classic Period in the Petexbatun, Guatemala", which was the subject of a short review in the online edition of USA Today last Saturday, November 8, 2008. As Emery's research shows, a dietary resource depression does not seem to have been a contributing factor to the abandonment of the Petexbatun region (edited by MNU):

Did environmental disasters play role in Mayan decline? - Apocalypto fans might be forgiven for thinking the fabled collapse of the ancient Maya, the retreat of a civilization from pyramids and ceremonial centers across Central America from 800 to 1000 A.D., involved all sorts of cataclysmic events, war, famine and devastation. Jared Diamond's Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed detailed how environmental disasters might be to blame, a popular scholarly explanation for the Maya collapse. "These models suggest that as ecosystems were destroyed by mismanagement or were transformed by global climatic shifts, the depletion of agricultural and wild foods eventually contributed to the failure of the Maya sociopolitical system," writes environmental archaeologist Kitty Emery of the Florida Museum of Natural History in the current Human Ecology journal.

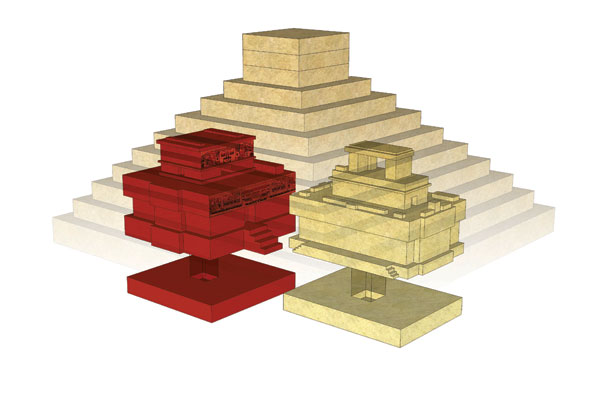

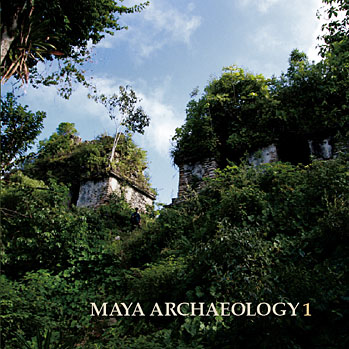

But in that case, she asks in her study, what do the archaeological remains of what the Maya ate tell us about the collapse? To find out, Emery looked to the precious archaeological resources offering the keys to the past. "We looked mostly at garbage pits," Emery says, 460 of them, left over from former centers of the Petexbatun region of Guatemala, "right in the heart of the central lowlands" where the Maya lived. Petexbatun [...] is best known for the abandoned pyramid centers of Dos Pilas and Cancuen investigated by a group led by Vanderbilt University's Arthur Demarest for more than a decade. Sorting through trash heaps in the region, Emery and colleagues have collected the bones, shells and scraps thrown away by the Maya who once lived near these sites.

Emery looked at game animal remains from white-tail deer, red brocket deer and peccaries (small pig-like critters native to Central America) to see if the hunting went south on the Maya before the collapse. Did the Maya switch to less tasty animals as the collapse neared and the larder went bare? Not so much, the study reports. "Resource depression, if it existed in this region during the collapse periods, is reflected by the reduced availability of a single species (white-tail deer) and not the cadre of nutritionally significant prey. It was therefore not a significant factor in the political and social changes ("the Maya collapse") that occurred at the end of occupation in the Petexbatun region."

In fact, looking back at the animal remains dating back to the earliest era of Maya occupation in the region, about 600 B.C., the hunting in Petexbatun seems to have been okay for a long time. Whenever the elite at a site were bent on impressing the neighbors, through marriages, alliances or other means, they went hunting for white-tailed deer, "food that was associated with fertility, leadership and status," Emery says. "They were showing off. It's an old story."

The only time that hunting populations of large animals appear to have headed south, based on the garbage pits, is the earliest era, when the region was first colonized by the Maya, Emery says. "Pretty quickly, things stabilized and stayed that way, in what looks to have been a managed fashion, for a long time," she says.

Studies of human remains led by Texas A&M's Lori Wright have also shown scant evidence of dietary changes during the collapse period in Petexbatun, finding no evidence of the anemia of increased child mortality at two sites. However, other studies at the site of Copan have found increases in anemia around the time the site was abandoned.

So what happened in the collapse, at least in this part of the Maya world? "It was a bellicose place," Emery acknowledges, with evidence of warfare and walls across some ceremonial sites. "But the bodies aren't there," from any massive fighting, she says. More likely, there was just a political collapse in which rulers came to be seen over a two-century period as no longer delivering the goods, better crops or more rain.

Modern-day Maya still live relatively close to the abandoned sites, after all, descendants of the folks who lived there long ago. "Folks just melted away" from ceremonial centers, Emery says, just like people today changing rulers come election season (written by Dan Vergano; source USA Today - Science Snapshot).

But in that case, she asks in her study, what do the archaeological remains of what the Maya ate tell us about the collapse? To find out, Emery looked to the precious archaeological resources offering the keys to the past. "We looked mostly at garbage pits," Emery says, 460 of them, left over from former centers of the Petexbatun region of Guatemala, "right in the heart of the central lowlands" where the Maya lived. Petexbatun [...] is best known for the abandoned pyramid centers of Dos Pilas and Cancuen investigated by a group led by Vanderbilt University's Arthur Demarest for more than a decade. Sorting through trash heaps in the region, Emery and colleagues have collected the bones, shells and scraps thrown away by the Maya who once lived near these sites.

Emery looked at game animal remains from white-tail deer, red brocket deer and peccaries (small pig-like critters native to Central America) to see if the hunting went south on the Maya before the collapse. Did the Maya switch to less tasty animals as the collapse neared and the larder went bare? Not so much, the study reports. "Resource depression, if it existed in this region during the collapse periods, is reflected by the reduced availability of a single species (white-tail deer) and not the cadre of nutritionally significant prey. It was therefore not a significant factor in the political and social changes ("the Maya collapse") that occurred at the end of occupation in the Petexbatun region."

In fact, looking back at the animal remains dating back to the earliest era of Maya occupation in the region, about 600 B.C., the hunting in Petexbatun seems to have been okay for a long time. Whenever the elite at a site were bent on impressing the neighbors, through marriages, alliances or other means, they went hunting for white-tailed deer, "food that was associated with fertility, leadership and status," Emery says. "They were showing off. It's an old story."

The only time that hunting populations of large animals appear to have headed south, based on the garbage pits, is the earliest era, when the region was first colonized by the Maya, Emery says. "Pretty quickly, things stabilized and stayed that way, in what looks to have been a managed fashion, for a long time," she says.

Studies of human remains led by Texas A&M's Lori Wright have also shown scant evidence of dietary changes during the collapse period in Petexbatun, finding no evidence of the anemia of increased child mortality at two sites. However, other studies at the site of Copan have found increases in anemia around the time the site was abandoned.

So what happened in the collapse, at least in this part of the Maya world? "It was a bellicose place," Emery acknowledges, with evidence of warfare and walls across some ceremonial sites. "But the bodies aren't there," from any massive fighting, she says. More likely, there was just a political collapse in which rulers came to be seen over a two-century period as no longer delivering the goods, better crops or more rain.

Modern-day Maya still live relatively close to the abandoned sites, after all, descendants of the folks who lived there long ago. "Folks just melted away" from ceremonial centers, Emery says, just like people today changing rulers come election season (written by Dan Vergano; source USA Today - Science Snapshot).