Maya News Updates 2007, No. 16: Philadelphia - 25th Annual Maya Weekend at the University of Pennsylvania Museum

This year the Annual Maya Weekend at the University of Pennsylvania Museum celebrates its silver anniversary. The 25th edition of the Maya Weekend has as its subject

The Dawn of Civilization and it takes place on April 13 - 14, 2007. Information on the conference (schedule, program, abstracts for workshops and papers, registration, etc.) can be found at the website of the University of Pennsylvania Museum (

www.museum.upenn.edu).

For your convenience (and reading pleasure) here I include the abstracts of most of the papers that will be presented at this meeting (edited by MNU):

John Clark (Brigham Young University): Something Borrowed, Something New: A True History of Lowland Maya Civilization. Early Lowland Maya civilization arose about 600-300 BC and had its roots in late Olmec civilization, with its principal center located at La Venta, Tabasco. Numerous specific similarities between early Maya and late Olmec civilizations show that there must have been a relationship between the two, but, for the moment, archaeology has failed to reveal the missing historic links. The most obvious parallels between civilizations can be found in the institution of kingship and its physical manifestations and props. This paper focuses on this institution and other shared cultural practices and explores their significance for an epoch of co-history and synergism between the two civilizations. The first cause of Lowland Maya civilization was none of the usual suspects: population pressure, circumscription, warfare, trade, or climatic change. Rather, the prime mover of Maya Civilization was Olmec history – which early Lowland Maya peoples co-opted as their own.

Ann Cyphers (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México): Wrestling with the Olmec. The Wrestler sculpture, allegedly from Antonio Plaza, Veracruz, Mexico, is without a doubt a masterpiece in basalt. Whether this piece may be attributed to the Olmec civilization (1200-400 BC) has been the subject of a recent debate (e.g. Kelker 2003; Coe and Miller 2005) in which its legitimacy is analyzed, but not resolved. The accurate evaluation of this sculpture, long held in high esteem for its beauty, has important repercussions for Olmec studies. If it can be demonstrated that this sculpture is legitimate, it may be added to the corpus of stone icons that served as political emblems in the ancient Olmec landscape of the southern Gulf Coast lowlands. The distribution of these stone sculptures suggests the integration of a fluvial and terrestrial communication web that propitiated interrelationships and interactions in social, economic and political frameworks.

Francisco Estrada-Belli (Vanderbilt University): Highland-Lowland Interactions and the Emergence of Maya States. In this talk I will address the relationship between the Maya Lowland and Highland regions as these relate to the rise of Maya states. I will first outline how earlier scholars have linked the rise of Maya states to two hypothesized migratory movements from the highlands to the lowlands. The first migration is the one that brought farmers into the lowlands at the onset of the first millennium BC. The second migration is the one that brought polychrome ceramics and hieroglyphic writing into the lowlands during the Terminal Preclassic period (ca. A.D. 150-250). The arrival of Teotihuacan iconography on Early Classic carved monuments was once believed to reflect a third possible migration that brought state-level organization to the Lowlands. As it is now widely recognized, the appearance of such iconography post-dates the emergence of Maya states. These diffusionists models are unsupported by current data. I will contrast the migration models with current data to show that much more can be said now about Preclassic period developments in the Maya Lowlands than previous models had allowed for. The new data show a much deeper chronology of occupation for the Lowlands and a much earlier point of departure for the development of state-level civilization in this region than previously thought. While communication between the Maya people of the highland and lowland regions was undeniably constant, the current data suggest that the development of civilization in the Lowlands was more independent from major migratory movements and cultural inputs from more developed regions than previously thought.

David C. Grove (University of Florida): From Tlatilco to Teotihuacan: the Foggy Dawn of Civilization in Central Mexico. This presentation takes a close look at the archaeological data behind the myths and realities of the rise of urbanism in central Mexico. It raises the question, was civilization there built upon an Olmec legacy? An examination of the Preclassic archaeological record at the sites of Tlatilco, Chalcatzingo, Cuicuilco and Teotihuacan demonstrates significant changes in interregional interactions and influences over time. Social and natural forces affecting the region's Preclassic period populations are also discussed. This chronological overview reveals that the archaeological record pertaining to the dawn of civilization in central Mexico is obscured by significant data gaps. Current popular interpretations may have over-simplified a very complex situation and likewise overlooked some significant data.

Julia Guernsey (University of Texas at Austin): The Preclassic Period along the Pacific Slope: Monuments, Themes, and New Discoveries. This talk explores recent discoveries along the Pacific coast and piedmont of Guatemala and Mexico and considers them within the long-standing traditions of carved monuments and impressive architectural spaces that characterized this region during the Middle (900 – 300 BC) and Late (300 BC – AD 250) Preclassic periods. It will focus in particular on a series of monuments and themes that were consistently invoked in this region for over a millennium at a variety of sites. It will also explore how rulers manipulated specific symbols not only to assert their political authority, but also to underscore their ability to communicate with the supernatural realm. The talk will also consider how these symbols and themes known from the Pacific region were part of broader systems of communication that were shared between other regions of Mesoamerica including the Central Mexican highlands and the Maya lowlands.

Norman Hammond (Boston University): “A Back-Looking Curiosity”: The Maya Middle Preclassic In Middle-Distance Perspective. The period from 700 to 400 BC, the late Middle Preclassic, is one of the most crucial research topics in Maya archaeology today: here lies the key to the genesis of Maya civilization” (Hammond 1986: 402). Twenty-one years ago that view seemed extreme to some, with the Middle Preclassic still often regarded as a period when simple villagers grew corn and beans in milpas cut freshly from the forest: today, new material from a variety of sites shows us that while Preclassic Maya civilization may have attained literacy and developed iconography encoding its belief systems only after 400 BC, substantial progress towards a complex society had been made in the preceding three centuries.

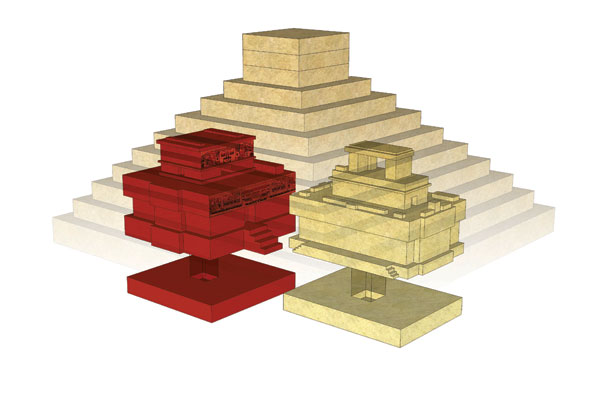

Richard D. Hansen (Idaho State University & FARES): New Cultural and Natural Perspectives on the Dawn of Maya Civilization in the Mirador Basin. Scientific investigations from 19 sites in the Mirador Basin have provided new perspectives on the origins and cultural and ecological dynamics of incipient Maya civilization. Settlement distributions of Maya sites show a strong correlation to major bajo systems which have precipitated a series of studies of the natural and geologic history of the area. Significant variations in climatic and settlement concentrations have altered the ecological landscape and had significant impact on wetland marsh systems which formed the economic engines of the prodigious growth of the Preclassic Maya in the Mirador Basin. The impacts were followed by social and political unrest which fueled additional stress on the political and economic systems in place. The resultant data provide a model to explain the rise and demise of early complex societies in the tropical forest environment of the northern Petén. Observations of the subsequent modest populations in the Mirador Basin during the Late Classic period, nearly a thousand years later, provides a test case for the hypotheses generated by the data.

Eleanor King (Howard University): Sweat Equity: The Role of Labor in the Birth of the Maya State. It has become axiomatic among scholars researching the origins of complex societies that social differentiation first developed because emerging elites were able to control scarce and/or critical economic resources. The question is what resources did they control? From China to Oaxaca archaeologists have postulated that power was based on ownership of land and natural resources such as metal ores or obsidian. Hand in hand with ownership went elite control over the production and distribution of goods from those sources, whether in the form of agricultural surplus, raw materials, or finished craft items. Among the Maya, however, the economic resource that was most valued seems to have been human labor. This presentation will examine the implications of that emphasis for the early development of social inequalities in the Maya area. Of particular interest will be the organization of labor surrounding different productive activities and the interaction between labor, natural resources, and trade in the creation of Maya elites.

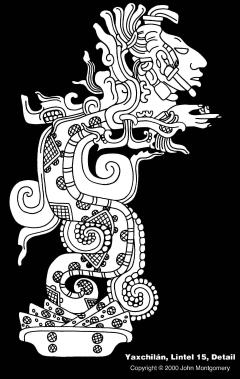

Simon Martin (University of Pennsylvania Museum): Early Maya Kingship: The Control of Word and Image. When we investigate the earliest stages of Maya statehood we concern ourselves with how systems of political authority evolved and came to control significant populations and territorial domains. This paper examines the earliest examples of royal portraiture and hieroglyphic inscriptions for clues to these processes. Underlying it are questions about how these manifestations are controled by early states and how the hazy image of the Preclassic state they allow might be resolved into a comprehensible system. Late Preclassic civilization (400 BC-AD 200) developed many facets of the personalized power that achieved its fullest form in the Classic period (AD200-900), but important questions remain about how closely these two eras can be compared. We need to ask how real our modern division into eras really is, and whether the transition is better characterized as an revolution, evolution, or one that amounts to little difference at all.

Karl Taube (University of California at Riverside): Ritual And Mythology Of The Late Preclassic Maya: An Overview. It is becoming increasingly clear that Preclassic Maya culture and society was by no means a simpler, inchoate precursor to the glories of the Classic Maya. Instead, Late Preclassic art and monumental architecture indicate the great political power and cultural complexity of Maya society at this early date. For the highlands and piedmont region of Guatemala and neighboring Chiapas, stone monuments from such sites as Izapa, Talalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu bear complex scenes and texts pertaining to Late Preclassic Maya ritual and belief. In addition, many lowland Maya sites, including El Mirador, Uaxactun, Tikal and Cerros contain monumental architecture with impressive stucco facades of gods and ancestral beings. The recent discovery of well-preserved, Late Preclassic murals at the site of San Bartolo, Guatemala, promises to radically change our understanding of the Late Preclassic period and the development of Maya religious traditions. The finely painted murals are virtually a "codex of creation," and depict detailed scenes of early Maya mythology. Partly through the prism of San Bartolo, this study will examine how Late Preclassic Maya religious practices and belief are manifested and transmitted through art and monumental architecture. Among the themes to be discussed are mythology and deities, including the rain, maize and sun gods, ritual practices including dance, deity impersonation and human sacrifice, and concepts concerning ancestral souls and the afterlife.

Marcello Canuto (Yale University): Does the Sun Always Rise in the Southeast? The development of complexity in Maya civilization has been recently invigorated by a series of spectacular finds in the lowland regions of Veracruz and Peten. These have demonstrated the precocious development of complexity among lowland relative to highland Mesoamerican societies. These discoveries emphasize the use of mature writing systems and the formation of formal political hierarchies centuries earlier than once believed. However, one cannot preclude the existence of increasing social complexity elsewhere in the Maya area based solely on the absence of the more immediately recognizable material indices of political hierarchy. Given the absence of similar evidence of ancient complexity in the southeastern Maya area, the development of social complexity in this area has often been interpreted as a consequence of external influences from neighboring areas exhibiting greater complexity. It is indeed true that evidence for eternal contacts in the southeastern Maya area (Mixe-Zoquean colonists, Olmec merchants, highland Maya traders, or Cholan speaking Maya settlers) is rife and pertinent to the area's development. However, the question of this region's social complexity is not fully explained by these external contacts. Rather, social complexity in this area developed through alternative mechanisms that did not result in easily recognizable archaeological indices, but were nonetheless equally transformative. New data from the Copan, El Paraíso, and other western Honduran valleys will be presented and synthesized to assess the rise of complexity in an area that has traditionally been dismissed as peripheral.

Michael Love (California State University at Northridge): The rise of the south: The southern Maya region in the Middle and Late Preclassic. The Late Preclassic period was in many ways a demographic and cultural climax in the southern Maya region. Many portions of the coast and highlands reached population levels not seen again until modern times, and state-level polities may have developed throughout the area. Early Maya art and hieroglyphic inscriptions, including a majority of the known Baktun 7 Long Count dates in Mesoamerica, are found in the region at this time. This paper will provide an overview of the Middle to Late Preclassic period within the region, with an emphasis the transition from La Blanca to El Ujuxte in the southwestern Pacific coast. Data from household contexts, ceremonial zones, and regional survey together show three keys areas in which La Blanca and Ujuxte differed: economics, ideology, and daily practice. First, the elite at Ujuxte wielded more effective economic control by centralizing storage of subsistence resources while also more effectively controlling long-distance exchange. Second, the elite transformed ideology by two means; a) the primary locus of ritual activity was moved from the household to public areas where the elite controlled the agenda, b) by asserting new ideological claims that they serve as a center essential to cosmological order and reproduction. Third, the transformation of material culture, especially monumental architecture, served to create daily social practices that reinforced increasing social inequality.

Also William Saturno (University of New Hampshire) will present a paper at the 25th Annual Maya Weekend, but at present no abstract was available.