Maya News Updates 2007, No. 63: Aguateca - Archaeological Evidence Suggests That Maya Elite Made Its Own Personal Items

On Wednesday August 29, 2007, the online University of Florida webservice Inside FU posted a report on archaeological research at the Guatemalan site of Aguateca which suggests that Maya elite prepared its own personal items of bone, shell, and other materials. The study was led by Florida Museum of Natural History's environmental archaeologist Kitty Emery and the results were published in the most recent issue of Ancient Mesoamerica (edited by MNU):

Florida Museum-led study counters ideas about Mayan elite craftworks - A new Florida Museum of Natural History study shows ancient Maya political elites likely crafted their own bone and shell products for domestic use, which counters previously held beliefs that the group depended on domestic servants or lower classes for everyday household items such as sewing pins, spatulas and shell bowls.

The study in the August 14, 2007, print edition of the journal Ancient Mesoamerica provides clues to ancient Maya society and offers new insight into how elite status groups used and controlled animal bone and shell resources, says lead author Kitty Emery, an environmental archaeologist at the Florida Museum on the University of Florida campus. “It is extremely difficult for archaeologists to establish strong links between the artifacts we excavate and the specific people who made or used them, but the unique preservation at this site provided us a rare break,” Emery said. “Because the city was abandoned so rapidly we’ve been able to pinpoint, for the first time, exactly who was doing what with bone and shell products among the upper classes and rulers of the Maya world.”

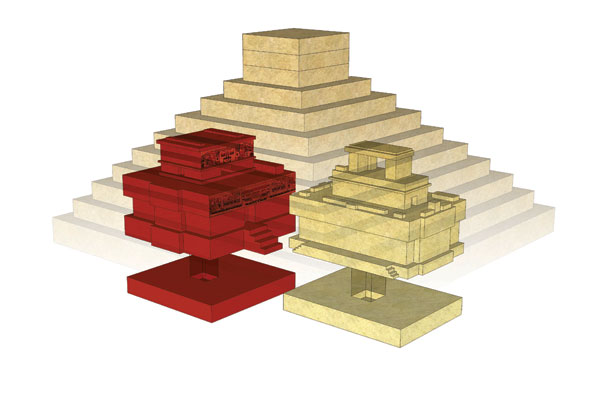

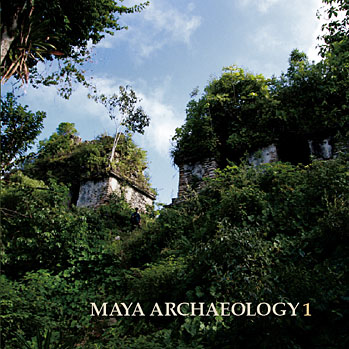

The study included extensive analysis of more than 20,000 bone and shell craft items and the stone tools used to make them. Scientists excavated the artifacts from elite homes in the core of the medium-sized ancient Maya city of Aguateca, located in the Petén region of the lowlands of modern-day Guatemala. Aguateca was one of the most politically important cities of the Petexbatún region. An invasion of the city in about 830 A.D. set in motion a series of events leading to its very unusual preservation. Despite stone-wall reinforcements around the region where the elite lived, the invasion was so sudden that the powerful ruling class fled for their lives. In their haste, they left belongings scattered in their homes.

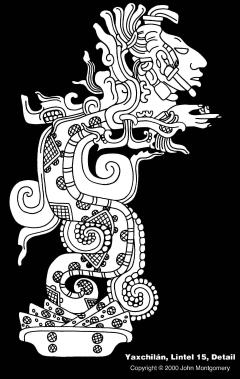

“The invaders burned the homes and as the structures caved in and the walls collapsed, they encapsulated a snapshot of the elite’s daily activities,” Emery said. “Conditions for preservation are normally poor in these lowlands, so this is unique. This is the first time we’ve been able to link a specific status group with the actual stone tools used to make individual bone and shell products.” Based on glyphs in ancient Maya writing and artistic scenes depicted on vases, most archaeologists accept that the Maya elite were likely involved at some level in luxury craftworks, such as body and clothing adornments. But Emery’s study is the first to assert they also were making everyday household bone and shell crafts for their own use — or that of the community, or their rulers — such as awls, needles, pins, disks, plaques, carved-bone segments, tubes, rasps, paintbrush holders, bone hooks and grinders.

The site was excavated between 1989 and 1996 by the Aguateca Archaeology Project, directed by Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan of the University of Arizona. Emery analyzed the bone and shell items and their distributions between 1991 and 2004, in large part at the Florida Museum. Co-author Kazuo Aoyama of Ibaraki University in Japan analyzed the stone tools, and all the artifacts were returned to Guatemala. Emery’s prior research at Dos Pilas, an ancient Maya community near Aguateca, produced detailed records of the stages of bone and shell craft production, which she used to interpret the remains excavated in Aguateca. Co-author Aoyama’s prior studies of tell-tale microwear patterns etched into stone tools from repeated use (such as cutting leather, skinning and butchering animals, or shaping stone, bone or shell) also aided their interpretation.

“Without this backdrop of comparative evidence, and without linking Aoyama’s previous research with mine, we wouldn’t have been able to interpret the Aguateca elite activities in such detail,” Emery said. “Critics may counter the elite could have had domestic servants or independent artisans doing these activities, but the weight of the cumulative contextual evidence points to crafts being produced at every level of the elite class. Even the king’s family was working on final-stage production of things like shell adornments and leatherworking.”

Excavation work at the site has produced no evidence that other parts of the city were attacked before its ultimate abandonment. This was typical of Maya warfare tactics, Emery explained. “The ancient Maya saw cities as animate beings, and if you wanted to kill a city you went straight for its spirit, or its leaders,” she said.. “Once the leaders were dead, the political power of the city was defeated. They considered it unnecessary to kill the lower classes.” The ancient Maya also considered residences and buildings as animate beings, and their spatial layouts often symbolically reflected the left-right dichotomy of the human body. Modern ethnography indicates that past and modern Maya cultures associate the left side of residences with women and the right side with men.

Emery’s team consistently excavated certain craft activities in right- and left-side auxiliary chambers adjacent to a central room, leading her to hypothesize that women were executing the early stages of bone and shell crafting. Evidence for final-stage crafting, such as nearly finished adornments, was found in chambers associated with men, Emery said. This study is one component of Emery’s more extensive research at Aguateca and other sites in Guatemala and Honduras detailing the courtly and humble lives of the ancient Maya throughout the Classic Maya time period.

She currently is tracing pathways of how animal products such as meat, bone, and shell entered Maya communities, how they were circulated and who controlled their production and distribution. Answers to these questions will help Emery and other scientists better gauge human impact to the lowland Maya environment, including effects on animals from hunting (written by DeLene Beeland; source InsideFU).

The study in the August 14, 2007, print edition of the journal Ancient Mesoamerica provides clues to ancient Maya society and offers new insight into how elite status groups used and controlled animal bone and shell resources, says lead author Kitty Emery, an environmental archaeologist at the Florida Museum on the University of Florida campus. “It is extremely difficult for archaeologists to establish strong links between the artifacts we excavate and the specific people who made or used them, but the unique preservation at this site provided us a rare break,” Emery said. “Because the city was abandoned so rapidly we’ve been able to pinpoint, for the first time, exactly who was doing what with bone and shell products among the upper classes and rulers of the Maya world.”

The study included extensive analysis of more than 20,000 bone and shell craft items and the stone tools used to make them. Scientists excavated the artifacts from elite homes in the core of the medium-sized ancient Maya city of Aguateca, located in the Petén region of the lowlands of modern-day Guatemala. Aguateca was one of the most politically important cities of the Petexbatún region. An invasion of the city in about 830 A.D. set in motion a series of events leading to its very unusual preservation. Despite stone-wall reinforcements around the region where the elite lived, the invasion was so sudden that the powerful ruling class fled for their lives. In their haste, they left belongings scattered in their homes.

“The invaders burned the homes and as the structures caved in and the walls collapsed, they encapsulated a snapshot of the elite’s daily activities,” Emery said. “Conditions for preservation are normally poor in these lowlands, so this is unique. This is the first time we’ve been able to link a specific status group with the actual stone tools used to make individual bone and shell products.” Based on glyphs in ancient Maya writing and artistic scenes depicted on vases, most archaeologists accept that the Maya elite were likely involved at some level in luxury craftworks, such as body and clothing adornments. But Emery’s study is the first to assert they also were making everyday household bone and shell crafts for their own use — or that of the community, or their rulers — such as awls, needles, pins, disks, plaques, carved-bone segments, tubes, rasps, paintbrush holders, bone hooks and grinders.

The site was excavated between 1989 and 1996 by the Aguateca Archaeology Project, directed by Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan of the University of Arizona. Emery analyzed the bone and shell items and their distributions between 1991 and 2004, in large part at the Florida Museum. Co-author Kazuo Aoyama of Ibaraki University in Japan analyzed the stone tools, and all the artifacts were returned to Guatemala. Emery’s prior research at Dos Pilas, an ancient Maya community near Aguateca, produced detailed records of the stages of bone and shell craft production, which she used to interpret the remains excavated in Aguateca. Co-author Aoyama’s prior studies of tell-tale microwear patterns etched into stone tools from repeated use (such as cutting leather, skinning and butchering animals, or shaping stone, bone or shell) also aided their interpretation.

“Without this backdrop of comparative evidence, and without linking Aoyama’s previous research with mine, we wouldn’t have been able to interpret the Aguateca elite activities in such detail,” Emery said. “Critics may counter the elite could have had domestic servants or independent artisans doing these activities, but the weight of the cumulative contextual evidence points to crafts being produced at every level of the elite class. Even the king’s family was working on final-stage production of things like shell adornments and leatherworking.”

Excavation work at the site has produced no evidence that other parts of the city were attacked before its ultimate abandonment. This was typical of Maya warfare tactics, Emery explained. “The ancient Maya saw cities as animate beings, and if you wanted to kill a city you went straight for its spirit, or its leaders,” she said.. “Once the leaders were dead, the political power of the city was defeated. They considered it unnecessary to kill the lower classes.” The ancient Maya also considered residences and buildings as animate beings, and their spatial layouts often symbolically reflected the left-right dichotomy of the human body. Modern ethnography indicates that past and modern Maya cultures associate the left side of residences with women and the right side with men.

Emery’s team consistently excavated certain craft activities in right- and left-side auxiliary chambers adjacent to a central room, leading her to hypothesize that women were executing the early stages of bone and shell crafting. Evidence for final-stage crafting, such as nearly finished adornments, was found in chambers associated with men, Emery said. This study is one component of Emery’s more extensive research at Aguateca and other sites in Guatemala and Honduras detailing the courtly and humble lives of the ancient Maya throughout the Classic Maya time period.

She currently is tracing pathways of how animal products such as meat, bone, and shell entered Maya communities, how they were circulated and who controlled their production and distribution. Answers to these questions will help Emery and other scientists better gauge human impact to the lowland Maya environment, including effects on animals from hunting (written by DeLene Beeland; source InsideFU).

More on the Aguateca Archaeological Project and on environmental archaeology in general can be found at Kitty Emery's website.