Maya News Updates 2009, No. 32: El Mirador, Peten, Guatemala - Last Maya Stand of Pyramidal Summit?

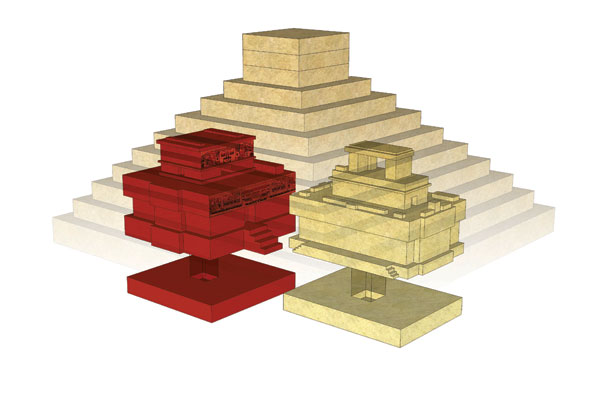

On Thursday September 3, 2009 (I have been extremely busy with too many things these last two weeks ...), the internatuional news service Reuters posted a press release on the site of El Mirad, Peten, Guatemala. The site is home to the largest pyramidal structure in the Maya area (the El Dante structure), but the release focusses on the discovery of some 200 obsidian tips, some having blood traces, as well as bone fragments and smashed pottery on the summit of the El Tigre structure. Possibly sokind of massacre had taken place here, possibly instigated by a Teotihuacan invasion force, the victims of which were local Maya driven to the summit of the structure. DNA tests are currently being undertaken of the blood traces. The obsidian was sourced in central Mexico (as the commentary to a Reuters video on the same subject states). Was this a last stand? Was the the end of the El Mirador site? (edited by MNU):

Guatemala Mayan city may have ended in pyramid battle - One of Guatemala's greatest ancient Mayan cities may have died out in a bloody battle atop a huge pyramid between a royal family and invaders from hundreds of miles away, archeologists say.

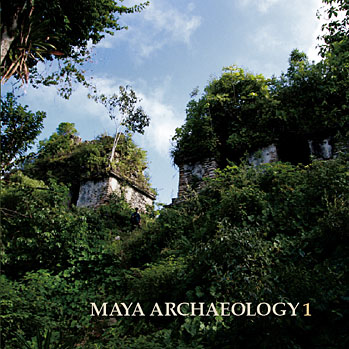

Researchers are carrying out DNA tests on blood samples from hundreds of spear tips and arrowheads dug up with bone fragments and smashed pottery at the summit of the El Tigre pyramid in the Mayan city of El Mirador, buried beneath jungle vegetation 5 miles (8 km) from Guatemala's border with Mexico.

Many of the excavated blades are made of obsidian which the archeologists have traced to a source hundreds of miles away in the Mexican highlands. They believe the spears belonged to warriors from Teotihuacan, an ancient civilization near Mexico City and an ally of Tikal, which was an enemy city of El Mirador. "We've found over 200 of the obsidian tips alone, as well as flint ones, indicating there was a tremendous battle," said excavation leader Richard Hansen, a senior scientist in Idaho State University's anthropology department who is pushing the pyramid battle theory.

"It looks like this was the final point of defense for a small group of inhabitants," told Reuters. El Mirador is one of the biggest ancient cities in the Western Hemisphere and is thought to have been home to between 100,000 and 200,000 people at its height. Historians believe it was built up from around 850 BC and flourished for hundreds of years before it was mysteriously abandoned in 150 AD.

Many archeologists think the size and elaborate stucco decoration of the buildings in the city are to blame as the inhabitants used up stone, trees and lime plaster in their construction until their resources were entirely depleted. Hansen's team believes a group of some 200 people, thought to be the last remnants of the royal family, stayed in the ruined metropolis until they were attacked by warriors from Teotihuacan.

They believe the invaders were allies of Tikal, around 37 miles (60 km) to the southeast, which resented being dwarfed by the enormous pyramids of El Mirador and was eager to make sure the enemy never recovered. They think Teotihuacan warriors trapped the survivors in a siege before a bloody battle that sealed the city's fate.

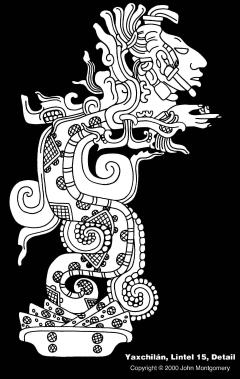

Hansen's archeologists found graffiti they believe was left by Teotihuacan fighters who smashed up carved Maya monoliths and left crudely etched skull drawings, known as Tlalocs, on the rock as proof of their victory. "The Tlaloc is the war god image of the highland Mexicans (and we found it) crudely pecked on these monuments, suggesting that perhaps a hostile event had taken place here," Hansen said.

The team sent excavated spear tips to a lab in Missouri where scientists are trying to extract blood samples for DNA tests. They expect to find one DNA type in blood on the obsidian objects and a different type on the Maya-made flint fragments, suggesting a battle between two racial groups.

El Mirador is home to one of the world's biggest pyramids by volume, La Danta, named after the tapirs that roam the dense jungle that hid the pre-Columbian treasures for decades until the site was discovered in the early 20th century. American archeologists who made an aerial survey of the El Mirador Basin in Guatemala's northern Peten region in the 1930s mistook the tree- and vegetation-covered pyramid for a volcano.

Hansen has worked with teams digging at El Mirador for some 30 years. The site is at risk from looters, poachers and loggers trying to make a living out of the forest, as well as drug traffickers seeking to move cocaine into Mexico. Last year, President Alvaro Colom announced the creation of a huge park in the Peten region to encompass both El Mirador and the already excavated Tikal, a popular tourist site.

The park will include a silent propane-powered train to lug tourists to the El Mirador ruins, currently only accessible by helicopter or a two-day hike through the jungle (written by Sarah Grainger; editing by Catherine Bremer and Kieran Murray; source Reuters at Vision.org).

Researchers are carrying out DNA tests on blood samples from hundreds of spear tips and arrowheads dug up with bone fragments and smashed pottery at the summit of the El Tigre pyramid in the Mayan city of El Mirador, buried beneath jungle vegetation 5 miles (8 km) from Guatemala's border with Mexico.

Many of the excavated blades are made of obsidian which the archeologists have traced to a source hundreds of miles away in the Mexican highlands. They believe the spears belonged to warriors from Teotihuacan, an ancient civilization near Mexico City and an ally of Tikal, which was an enemy city of El Mirador. "We've found over 200 of the obsidian tips alone, as well as flint ones, indicating there was a tremendous battle," said excavation leader Richard Hansen, a senior scientist in Idaho State University's anthropology department who is pushing the pyramid battle theory.

"It looks like this was the final point of defense for a small group of inhabitants," told Reuters. El Mirador is one of the biggest ancient cities in the Western Hemisphere and is thought to have been home to between 100,000 and 200,000 people at its height. Historians believe it was built up from around 850 BC and flourished for hundreds of years before it was mysteriously abandoned in 150 AD.

Many archeologists think the size and elaborate stucco decoration of the buildings in the city are to blame as the inhabitants used up stone, trees and lime plaster in their construction until their resources were entirely depleted. Hansen's team believes a group of some 200 people, thought to be the last remnants of the royal family, stayed in the ruined metropolis until they were attacked by warriors from Teotihuacan.

They believe the invaders were allies of Tikal, around 37 miles (60 km) to the southeast, which resented being dwarfed by the enormous pyramids of El Mirador and was eager to make sure the enemy never recovered. They think Teotihuacan warriors trapped the survivors in a siege before a bloody battle that sealed the city's fate.

Hansen's archeologists found graffiti they believe was left by Teotihuacan fighters who smashed up carved Maya monoliths and left crudely etched skull drawings, known as Tlalocs, on the rock as proof of their victory. "The Tlaloc is the war god image of the highland Mexicans (and we found it) crudely pecked on these monuments, suggesting that perhaps a hostile event had taken place here," Hansen said.

The team sent excavated spear tips to a lab in Missouri where scientists are trying to extract blood samples for DNA tests. They expect to find one DNA type in blood on the obsidian objects and a different type on the Maya-made flint fragments, suggesting a battle between two racial groups.

El Mirador is home to one of the world's biggest pyramids by volume, La Danta, named after the tapirs that roam the dense jungle that hid the pre-Columbian treasures for decades until the site was discovered in the early 20th century. American archeologists who made an aerial survey of the El Mirador Basin in Guatemala's northern Peten region in the 1930s mistook the tree- and vegetation-covered pyramid for a volcano.

Hansen has worked with teams digging at El Mirador for some 30 years. The site is at risk from looters, poachers and loggers trying to make a living out of the forest, as well as drug traffickers seeking to move cocaine into Mexico. Last year, President Alvaro Colom announced the creation of a huge park in the Peten region to encompass both El Mirador and the already excavated Tikal, a popular tourist site.

The park will include a silent propane-powered train to lug tourists to the El Mirador ruins, currently only accessible by helicopter or a two-day hike through the jungle (written by Sarah Grainger; editing by Catherine Bremer and Kieran Murray; source Reuters at Vision.org).

Addendum: If anybody has an image of the "Tlaloc" graffiti, or the skulls, available and which can be posted here, these will be greatly appreciated.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home